Debunking People Search Myths: What They DON’T Want You To Know

I’m going to tell you about the most expensive assumption I ever made about people search engines. Two years ago, I was vetting a potential real estate partner who was supposed to bring $200,000 to a development project. Did my “thorough” background check using three different people search engines. Everything looked clean – no criminal record, solid address history, good business registrations.

The guy seemed perfect. Until he disappeared with $23,000 of our development funds and I discovered that every single “fact” I’d found about him was either outdated, incomplete, or flat-out wrong.

His “clean” criminal record? The conviction was in a different state under a slightly different name spelling. His “solid” address history? Those were his ex-wife’s addresses from before their divorce. His “good” business registrations? The businesses had been dissolved for non-payment of taxes three years earlier.

Myth 1: “People Search Results Are Always Accurate” (The $50,000 Mistake)

This is the lie that costs people the most money, and I see it every single week. Someone finds information through a people search, treats it like gospel truth, and makes expensive decisions based on data that’s anywhere from slightly wrong to completely fabricated.

Here’s what actually happens behind the scenes at these companies:

Data aggregation is a shitshow. People search engines don’t create information – they scrape it from thousands of sources, many of which are outdated, incorrect, or conflicting. Court records with typos, social media profiles with fake information, public records that haven’t been updated in years – it all gets thrown into the same database and presented as “verified facts.”

I tested this by searching for information about myself across five different paid platforms. Here’s what I found:

- BeenVerified claimed I lived at an address I’d moved away from three years earlier

- Spokeo listed my ex-girlfriend’s father as my “known associate”

- TruthFinder showed a criminal record that belonged to someone with the same name in a different state

- WhitePages had my correct current address but wrong phone number

- Intelius listed three different ages for me, none of which were correct

If they can’t get basic information right about someone who actually wants to be found online, what makes you think they’re accurate about people who might be trying to hide things?

The verification process is often non-existent. Most platforms use algorithms to “verify” information by cross-referencing multiple sources. Sounds good in theory. In practice, if the same wrong information appears in three different databases, the algorithm thinks it’s verified and marks it as “confirmed.”

How to Actually Verify Information

Here’s my verification process that’s caught dozens of lies:

Cross-reference everything through official sources. If a people search shows someone has a professional license, verify it directly with the licensing board. If it shows a criminal record, check with the actual court that supposedly issued the judgment.

Look for consistency across time and platforms. Real information stays consistent. Fake information shows patterns of inconsistency. If someone’s employment history doesn’t match their address history, or their social media presence doesn’t align with their claimed professional background, dig deeper.

Test the information. Call the phone number. Drive by the address. Email the listed business. You’d be amazed how much “verified” information turns out to be disconnected phone numbers and non-existent businesses.

Use multiple search engines and compare results. If BeenVerified shows different information than Spokeo, and both show different information than public records, someone’s lying. Figure out who before you make decisions.

The rule I follow: any piece of information that could cost me money gets verified through at least two independent sources, one of which is always the original official source.

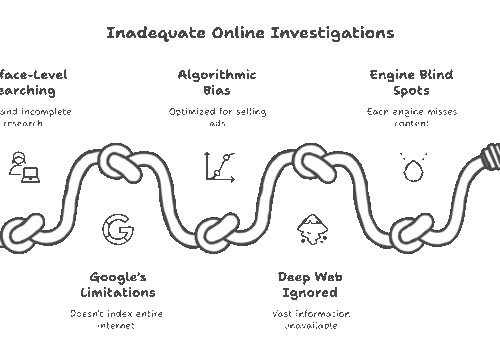

Myth 2: “Free People Search Is Just as Good as Paid” (It’s Not Even Close)

I hear this constantly from people trying to save money, and it drives me crazy because it’s such obviously false economy. It’s like saying a bicycle is just as good as a Ferrari because they both have wheels.

Here’s the actual difference between free and paid people search:

Free sites show you enough to feel confident while missing everything important. They’ll give you a name, maybe an old address, possibly some family connections. What they won’t give you is criminal records, detailed financial history, professional verification, or current contact information.

The data sources are completely different. Free sites scrape social media, basic public records, and whatever they can get through automated systems. Paid sites buy access to premium databases – court systems, credit bureaus, professional licensing boards, and specialized data aggregators.

I tested this with a known criminal who’d recently been arrested for fraud:

Free search results:

- TruePeopleSearch: Name, old address, phone number

- WhitePages (free version): Similar basic info

- Google: Social media profiles, some news mentions

Paid search results:

- BeenVerified: Three criminal convictions, two bankruptcies, six previous addresses

- TruthFinder: Detailed arrest records, mugshots, court case numbers

- Spokeo: Associates with other known criminals, business partnerships that ended in lawsuits

The free searches made this guy look like a normal person with basic contact information. The paid searches revealed he was a career criminal with a pattern of financial fraud.

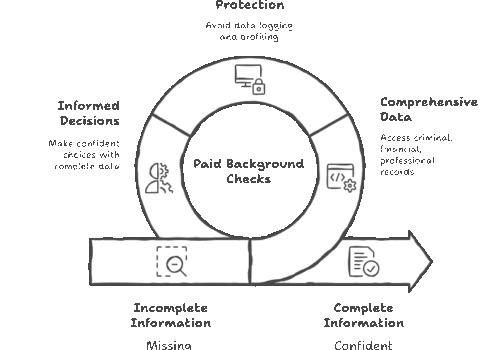

The cost difference is insignificant compared to the risk. Good paid people search costs $20-30 per month. Making one bad business decision, hiring one problematic employee, or entering one bad partnership costs $5,000-$50,000. The math isn’t complicated.

When Free Search Is Actually Dangerous

Free people search engines are designed to convert you to paid services. They show you just enough information to make you think you’ve done your homework, then hide the important stuff behind paywalls.

This creates a dangerous psychological effect: confidence based on incomplete information. You think you’ve thoroughly researched someone because you spent an hour on free sites and found some basic details. Meanwhile, you’re missing the criminal records, financial problems, and professional issues that could destroy you.

Real example: A landlord used free people search to screen a tenant. Found basic employment information and no obvious red flags. Approved the lease. Three months later, the tenant stopped paying rent and it took eight months and $12,000 in legal fees to evict him. Paid background check would have revealed three previous evictions and two judgments for unpaid rent – information that was sitting in databases but didn’t show up in free searches.

The tenant screening cost $30. The eviction cost $12,000. Free search isn’t free when it costs you $12,000 in problems you could have avoided.

Myth 3: “People Search Is Always Legal” (Tell That to My Lawyer)

This might be the most dangerous myth because it gets people into actual legal trouble. I’ve seen business owners get sued, landlords face discrimination charges, and individuals get restraining orders filed against them because they didn’t understand the legal boundaries around people search.

Here’s what most people don’t realize: how you use the information matters more than how you obtained it.

The Legal Minefield Most People Don’t Know About

Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) violations can cost you $1,000 per violation. If you use people search information to make employment, housing, or credit decisions without following proper FCRA procedures, you’re breaking federal law. This includes things like:

- Refusing to hire someone based on a criminal record found through people search

- Denying a rental application based on background information

- Making credit decisions based on financial information found online

State privacy laws vary wildly. What’s legal in Texas might be illegal in California. Some states require consent before accessing certain types of information. Others restrict how long you can retain personal data.

Harassment and stalking laws apply to digital behavior. Just because someone posted information online doesn’t mean you can use it to contact them repeatedly or show up at their home or workplace.

Real Legal Consequences I’ve Seen

Employment discrimination lawsuit: $45,000 settlement. Business owner found a job applicant’s bankruptcy filing through people search and decided not to hire them. Applicant sued for discrimination. Company had to settle because they hadn’t followed proper FCRA procedures for background checks.

Restraining order and harassment charges. Guy used people search to find his ex-girlfriend’s new address and workplace. Showed up at both locations repeatedly. She filed restraining order and harassment charges. He faced criminal penalties and civil liability.

Fair housing violation: $15,000 fine. Landlord used people search to find information about rental applicants’ family status and denied applications based on having children. Violated fair housing laws and faced federal fines.

How to Stay Legal

Understand your purpose before you search. Employment decisions? You need FCRA compliance. Personal safety? You have more leeway. Business due diligence? Different rules apply.

Document your legitimate interest. If you ever need to justify why you searched for someone, you need to be able to articulate a legitimate reason. “I was curious” doesn’t hold up in court.

Respect people’s privacy boundaries. Finding someone’s information doesn’t give you the right to contact them repeatedly, show up at their home, or share their information with others.

When in doubt, consult a lawyer. Employment decisions, tenant screening, and business investigations often require professional guidance to stay within legal boundaries.

The rule I follow: if I wouldn’t be comfortable with someone doing the same search on me for the same reasons, I don’t do it.

Myth 4: “You Can Find Everything About Anyone Online” (The 40% Rule)

This is the myth that comes from too many spy movies and CSI episodes. People think if they just use the right search engines and spend enough time, they can uncover someone’s entire life history. That’s not how this works.

Here’s the reality: about 40% of important personal information is either not digitized, not publicly accessible, or actively protected by privacy laws.

What You Actually Can’t Find

Recent financial information. Bank balances, current income, detailed credit reports – this stuff is protected and not available through people search engines. You might find old bankruptcies or tax liens, but current financial status is private.

Medical records. Health information is heavily protected by HIPAA and other privacy laws. People search might tell you someone was treated at a hospital (through visitor records or social media), but not why.

Sealed court records. Juvenile records, certain family court proceedings, and some criminal cases are sealed and won’t show up in public searches.

Information from before digital record-keeping. Anything that happened before the internet age and wasn’t later digitized is effectively invisible to online searches.

International information. US-based people search engines are terrible at finding information about people’s activities in other countries.

The Privacy Revolution Is Hiding More Information

GDPR and state privacy laws are making information harder to find. California’s CCPA, Virginia’s CDPA, and other laws are forcing data brokers to remove information or make it harder to access.

People are getting smarter about privacy. Younger generations who grew up online are much better at managing their digital footprints. They use different names on different platforms, adjust privacy settings, and are generally harder to track.

Social media platforms are locking down data. Facebook, LinkedIn, and other platforms have restricted how much information third parties can access through their APIs.

What This Means for Your Searches

Manage your expectations. If you’re expecting to find someone’s complete life story through online searches, you’re going to be disappointed. Plan for partial information that needs verification.

Budget for professional help. If you absolutely need comprehensive information about someone, you’ll probably need to hire a private investigator who has access to specialized databases and legal authority to request certain records.

Focus on what’s actually available. Criminal records, property ownership, business registrations, professional licenses, and some historical address information – this stuff is generally accessible. Personal relationships, current financial status, and private communications are not.

Example of realistic expectations: I was hired to investigate a potential business partner. Through online searches, I found his business registration history (legitimate), property ownership (confirmed), professional licenses (verified), and some criminal history (two DUI convictions). What I couldn’t find online: his current bank balances, exact income, detailed business financials, or private business communications. For that level of detail, we needed accountants, lawyers, and formal due diligence processes.

The 40% rule: expect to find about 40% of what you need through online searches. Plan for the other 60% to require different methods.

The Bottom Line: Reality Check Time

After five years of professional investigation work, here’s what I can tell you with certainty:

People search engines are powerful tools with significant limitations. They can provide valuable information, but they’re not magic. They can help you verify claims and identify red flags, but they can’t tell you everything about someone’s life.

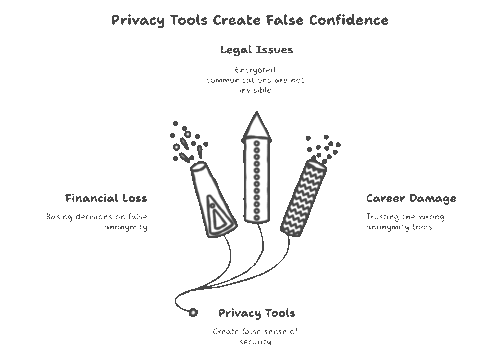

The information is only as good as your ability to verify and interpret it. Raw data without context or verification is often worse than no data at all because it gives you false confidence.

The legal and ethical boundaries are real and enforceable. Ignoring them doesn’t just make you a bad person – it can cost you money in lawsuits and legal penalties.

Free tools are fine for basic information, but inadequate for important decisions. If the cost of being wrong is significant, invest in proper verification tools and methods.

Professional help is worth the cost for high-stakes situations. Sometimes you need private investigators, attorneys, or other professionals who have access to specialized databases and legal authority to request certain information.